After Rubén Peréz, Tutto Mondo goes to the USA to interview Heather Cornell, an internationally renowned tap dancer and musician.

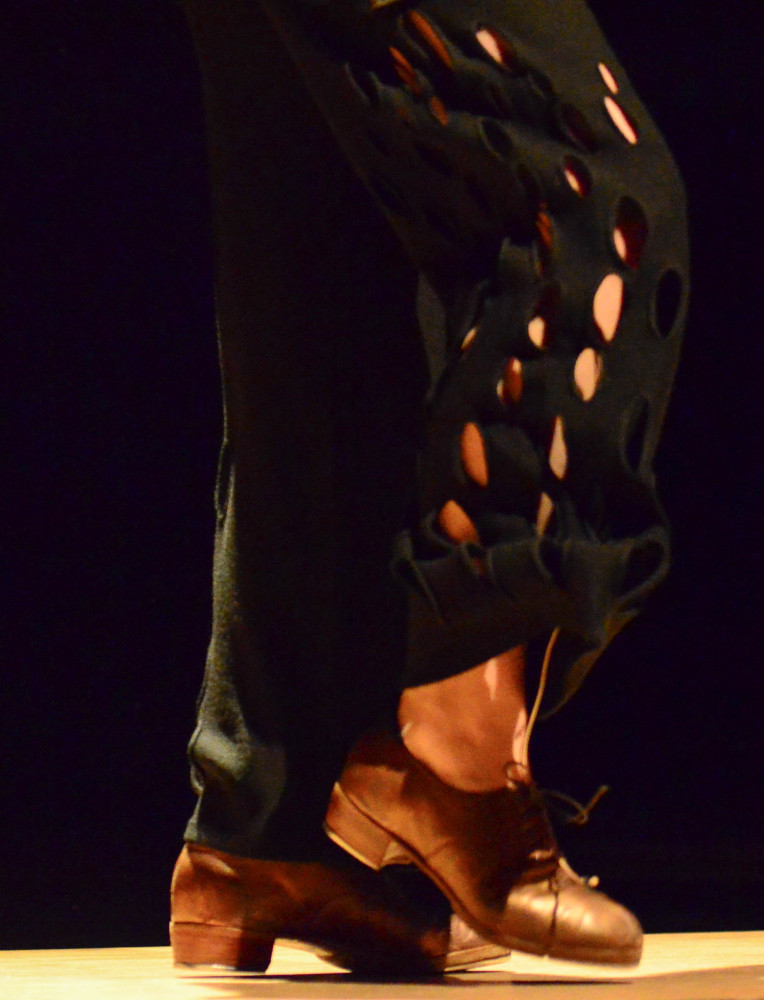

1. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell.

1. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell.

Heather Cornell is a Canadian artist based in Valley Cottage, NY. She is the Artistic Director of a number of music/dance companies, most notably Manhattan Tap and CanTap.

Among her most recent projects, she is famous for Making Music Dance with Andy Algire, Finding Synesthesia with Andy Milne (commissioned by London Jazz Festival), and Conversations (commissioned by Capilano University).

Heather Cornell trained directly with first-generation tap masters like Cookie Cook and Steve Condos and is the only tap dancer mentored by the infamous bassist, Ray Brown.

Hi Heather Cornell, thank you for the opportunity to take this interview.

What is tap dancing for you and what do you love about it?

«What I love about tap dancing is that it combines every aspect of performance: music, dance, and theatre. For me, tap dancing is an equally physical and musical experience with the addition of the theatrical element, and I love that it defines the history of theatre in North America.

Tap dance is the essence of the American vernacular theatre and is the thing that defines the vaudeville and early Broadway stages. Many of the big bands were fronted by tap dancers. If you look at some names like the Whitman Sisters, who had their show at the turn of the century (1899), they started their careers as dancers and musicians. If it weren’t for them we wouldn’t have the theatre that we have in America today and a large part of their vocabulary was tap dance. Alice Whitman was considered the best tap dancer in the business.

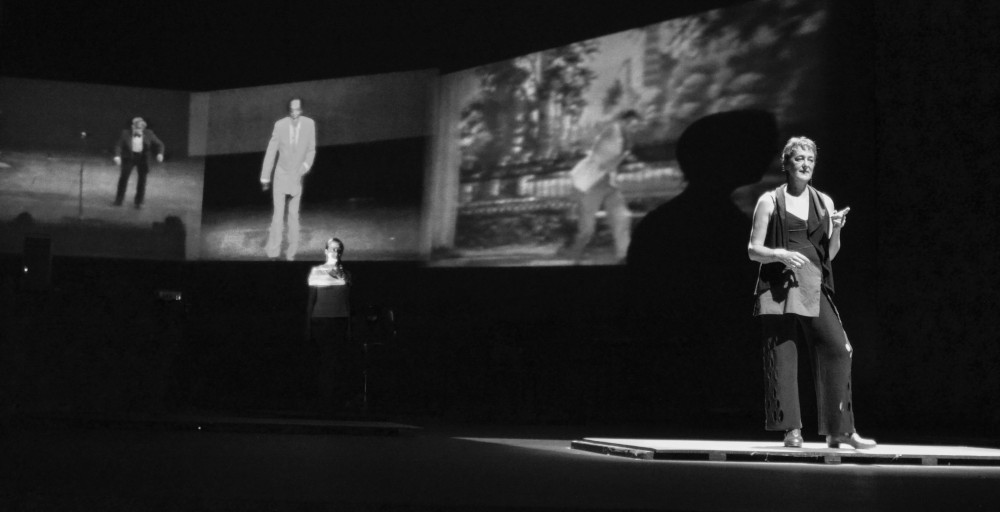

2. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell, copyright John F. Pastore.

Tap Dance is so important to the history of North America, both socially and culturally and it is misunderstood because of the cultural views by the society (racism, segregation), starting from Minstrel shows.

Tap dance is an art form that is very joyful for everyone who experiences it. It is just full of joy because of that balance of music and dance and theatre. It brings a lot of joy to a lot of people».

Which was your favourite show to dance into during your career and why? Any memories you want to share with us?

«They were all favorites. I mean, I did a show one time with Jackie Shue, Buster Brown, and Chuck Green. The show was with Chuck Green‘s favorite band, which was three singers and four musicians, and it was incredible.

I love the Manhattan Tap years because I loved being able to create, write, and collaborate with musicians and dancers on a such high level.

I loved the show with Ray Brown, it was a life-changing experience. But then, again, all my works after Manhattan Tap. Every single show I’ve created was really different. I love Can Tap because it was all Canadian and I was able to move things a little bit forward in my country of birth. And I loved Finding Synestesia with Andy Milne because that pushed me, shifted me further, and broke more barriers than any other show I have worked on, with the exception of my work with Ray Brown.

And then Making Music Dance is such a definitive voice for me. We got cut short due to CoVid. Everything shut down while we were working on the second CD. However, that experience of being on stage with like-minded and culturally diverse musicians, and the fact that it was multigenerational. – we had five different generations in a group of five. It fulfilled so many of my desires in terms of breaking barriers.

And there were some early works, like when I was a clown partner to Noel Parenti. When I was on Broadway choreographing The Play What I Wrote was an interesting experience. I don’t keep doing the same thing over and over again and every show that I do is a new child. You can’t pick your favorite child.

Good or bad, everything I have done has been a different experience and, you know, you can learn something from everything, you change».

Among your projects, Making Music Dance has a multi-generational music ensemble with tap shoes being fully integrated with the other instruments. How was working with all the musicians? Could you tell us more about the process behind the creation of Making Music Dance?

«I don’t think Making Music Dance would have ever happened without Finding Sinestesya happening first. Andy Milne was ready to stop and willingly commit to the process. We spent an entire week, 24 hours a day at the Banff Centre of Fine Arts in Canada. They gave us a studio with a grand piano and a tap floor. We found a collaborator there, Rebecca Birch, a video artist from England, who gave us these crazy wild videos. I had forced myself into a very difficult process that helped me to realize how much further I can go in my shows.

3. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell, copyright John F. Pastore.

With Making Music Dance, I reached out to the people around me because I was living upstate at the time and didn’t want to go to New York. The first group was the flamenco dancer, Anna de la Paz, Adriel Williams, Bobby Moses, and Andy Algire. Anna brought in a flamenco guitarist, Carlos Revollar, and the five of us hung out in my studio trying to find common ground. We had flamenco, violin, balafon, flamenco guitar, tap dance, sand dance and castanets as instruments. We worked to hear everything together and tried to find basic elements of common ground in order to collaborate with each other. The second year Anna left the show. She was less keen on improvisation than we were and she was also coming in conflict with the structures of flamenco. She didn’t want to break them whilst all we wanted was to creatively break structures.

So, Anna moved on and sadly we lost Carlos suddenly as he passed away. We brought in Antonio Vilchez, a zapateo dancer and cajon/cajita player and guitarist Tony Romano. We were then four generations with five people in the group and many different cultures and different cultural expressions represented. Andy was very big in the African community, Adriel in the Reggae community, and he also played Jazz. Tony played a lot of Latin Music and Antonio brought in his Afro-Peruvian background. Add to that my experience with dancing with the textures of tap, sand and wood.

We started composing, and we wrote one tune together. I also wrote one tune, but Andy and Adriel were the main composers. We brought in ideas, running through the cultural filters of the people in the room, and creating a new experience with the contribution of each instrument. It was very creative but it was hard because we were very different and very strong-willed. That said, when I was playing those shows I didn’t want to be anywhere else. The music was so perfect for me, it was exactly what I wanted to play, how I wanted to play. The primary percussions for this second group was tap dancing and zapateo, but this time Antonio also brought cajon and cajita to the table.

So then we had all kinds of voicings of percussions to play with as well as a guitar, violin, and balafon for the melody. And Adriel also added looping and m-base on his violin. I love the music, I listen to it and it makes me happy. I can listen to the music that we play all day long because is so rich, so full of voicing, so full of ideas, so full of culture and approaches. It is like a true community. It is kind of sad now that we are so distant at the moment. We are talking about bringing the band back together but it is harder now that we’ve all been scattered by CoVid.

4. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell, copyright John F. Pastore.

Another aspect of what I do is that I go into a community and create a show with people who are there. This started with a show in Vancouver. I was asked to create a show with the music and dance departments of Capilano College and we performed it at the North Shore Credit Union Centre for the Performing Arts in Vancouver. The show was called Conversations. It was very experimental and completely improvised. This was interesting to me after having Manhattan Tap for so many years, because was like switching to a different muscle. And it’s very different than say, going to a tap festival. Here you are going in as an independent artist and trying to reach a community, to get local people to play with and to create something together. It can be dangerous as you have not a lot of control over who things will work out, but it’s very fulfilling when it works».

Do you have any favorite tap dancers from yesterday and/or today?

«I am historically intrigued by the women because they simply didn’t get enough recognition and their names aren’t being spoken enough. Names like the Whitman Sisters. Many of the male dancers who I trained with, like Cookie, when I asked who they thought was the greatest Tap Dancer, didn’t say Bill Robinson but Alice Whitman. And then they say Oh, but Bill Robinson. I think women just get underplayed historically.

Jeni LeGon, I remember seeing her walking on stage and grabbing the audience immediately with her presence ,the second she was on stage, she was phenomenal. All of those women who came before me, I am grateful to them for starting the process of breaking down barriers in the community.

Eddie Brown was life-changing for me as standing beside him was like doing a Ph.D. in improvisation. But they were all important to me, Cookie, Buster, Steve and Chuck. Harriet Browne was phenomenal. They were all equally important.

One of the things about learning and teaching History is that history is not recording all of what happened but is recording the greatest hits, the things that were written or spoken about the most and so there are many facts that we probably never knew about.

5. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell, copyright John F. Pastore.

In the present day, I love lots of dancers that I am afraid to mention any of them because there are so many I will forget. I love Anthony, I love Travis, Thomas Wadelton, and so many others.

Inevitably when I teach a class there are a couple of dancers there that blow my mind, so it’s very hard to say one in particular. It is very important to mention that artists are everywhere, all around us. And it is important to keep repeating to dancers to be who they are, and to be unique. As long as we keep repeating that and people keep finding their way to that uniqueness we will keep having more and more phenomenal dancers Because tap dancers are a special breed.».

Let’s talk about Manhattan Tap, one of the prominent companies in the world of tap dance during the Eighties and the Nineties. How all has started? What were the aims of the company?

«It was a period where we were learning about history and about being professional tap dancers and there was nowhere to try anything out. We were learning such rich culture and art yet what could we do with it? We needed to put tap on stage to really understand what we were experiencing. And so we just started getting in a room to dance and make a show. We also danced on the streets for a while.

I was friends with Tony Scopino from Gail Conrad’s company, Shelly Oliver from York University, and Jamie Cunneen from Anita Feldmann‘s company. I was friends with all of them and they all wanted to do a duo with me. I thought of how cool it could be to put all our energies together and create something bigger. I invited all three together into the room, and we started rehearsing and very quickly it became clear that we could all be very good partners. The magic was definitely there. And, for me and Jamie, the bottom line was that we knew we had to work with live music. From day one we had a great music director, David Leonhardt, who was also the music director for Jon Hendricks at that moment.

6. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell.

So we started it because we wanted to work and our first show was in Toronto at the Toronto Dance Theater Studies. We immediately got two excellent reviews, which were difficult to get. We then went straight back to NYC and performed in the Clark Center festival at the Duke Theater. After two shows there we were offered an agent. They asked us if we had a show together, cause we were only doing a 20 min piece in the festival Rhythm Suite. We lied and said “sure!”.

I was coming out of a year touring with Jazz Tap Ensemble, and Fred Strickler was mentoring me. He gave us a gig with Lincoln Center’s touring program and we put together two casts with two dancers and two musicians each. We had to do 45 minutes for a show and so we got busy. Then we were in residence at the Riverside Theatre for two months and finally were able to put a whole show together. Cookie Cook was our guest artist. And that was how Manhattan Tap started.».

After your training as a modern dancer, you switched to tap dance. You literally trace back great artists of the caliber of Eddie Brown, Cookie Cook, Steve Condos, Chuck Green, and Harriet ”Quicksand” Browne and spend lots of time in the studios with them. What do you remember fondly about that period?

«Today you go to a festival, you pay for classes and then you learn from different teachers, everything is there for you. For us it was very different, there weren’t any festivals, there weren’t any classes. So we had to reach out to people and find these artists who eventually taught us. Cookie for example was teaching a one-hour class a week so I went to him and then of course the entire world unfolded to me after meeting him. He introduced me to the tap community. When you went to Cookie‘s class, guys from the Copasetics were there every now and then, or a famous performer I had seen on the Ed Sullivan show, so you could experience the community in the room. It was a very tiny community.

In the eighties we were a handful of people studying with Cookie, others were studying with Brenda Bufalino and Peggy Spina. People back then didn’t seem to move around that much. I took maybe one class with Brenda and I realized immediately it wasn’t my thing, Cookie was my thing. He was more swing music-oriented while Brenda was more into the whole concept of orchestra, which is the classical model. I was really into having the form vs chaos of jazz so I was reaching out to anybody that really reinforced that. Being in the room with Cookie was full of swing and I learned so much about jazz standards. I really got into melodic dancing from my time with him.

I didn’t study much with Buster Brown but we hung out a lot as friends, and he toured with my company. Once in a while though we’d jam together in a studio. That is where I really started to swing – from Buster. Buster was a man of swing. Steve Condos was coming in and out, I mostly hung out with him at festivals or when we were on the same gigs. Steve was just so passionate and he was so committed to his concept of the rudiments and the drumming. I learned to divide the beat and to think like a drummer. From Steve. But again, I wasn’t there for the technique, I wasn’t thinking that way. For me, it was all about the musical aspect. Chuck Green was more like being around this incredible, illusive, creative mind. You could learn from all of them just by being in their wake.

7. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell, copyright John F. Pastore.

And then I met Eddie Brown, and that is when I started learning to balance technique and improvisation. But Eddie was kind of tragic and beautiful at the same time as he was a struggling alcoholic. He was one of the most creative people I have ever met. He was the most fluid improviser I have ever seen».

Last but not least important, What are your plans for the future?

«I have the Tap Legacy project. The goal is to disseminate knowledge, history, and my archives to the largest demographic possible without losing the inherent oral traditions. I am trying to find a way to nurture the importance of mentorship in choreography. This is one of our weak spots, we don’t have any consistent training for choreographers. Every now and then a strong choreographer pops up but we don’t have any consistent training in this field.

I am trying to rebalance the pedagogy of tap. One of the main problems that we have is the unbalance in terms of music and dance training. Because we keep calling it a dance form, tap dance, the way that we train ourselves is based on the “ballet model”. We do lots of group classes where the main training of a musician is private classes, private practice and ensemble training. We need to get back to a balance of music and dance training. If you can’t ever hear yourself, how are you supposed to understand your own voice?

So I am really focusing on shifting the pedagogy, getting it out from the dance department into a place where we should exist, between the dance and music departments. I am fighting for that battle here. It is huge for me because I feel like we are not doing any service to our art form by allowing ourselves to be misclassified by what stemmed from the appropriation of the form. It is a musical-dance-theatre form that comes from the African-American diaspora. I am trying to find a way back to a pedagogy linked to vernacular jazz. And I think we all have to do a lot of work to make that happen.

Today I had a long conversation with my dancers about not counting 5 6 7 8 in the tap context and they were looking at me like “What does it matter?”. And it matters so much because it is a different language. 5 6 7 8 doesn’t exist in jazz music. So, why speak a different language? Why not speak the language of the art you are experiencing right now?

8. Photo by courtesy of Heather Cornell, copyright John F. Pastore.

I am also working on getting my memoirs done and getting my archive organized in order to create an access point for the next generations. I want to keep creating shows, which is what I have missed in the last three years. There are many more shows in me to put together and I would love to create a multigenerational company. I would love to see a tap dance company that honored all the styles from the beginning to where we are today but also honoring space, time, the distillation of techniques, and the musicality that you can only have with experience. I would love to have a multigenerational company like Manhattan Tap was, becoming at the end but to stretch each of the generations. Not a variety show of styles, but to actually inform and affect each other styles.

I want to look at tap dance in the broadest way possible, to imagine how many things tap dance has touched. Tap dance….music, theatre, and dance. When we embrace it all, what could be better? ».

We thank Heather Cornell for her time.

For more information about her work you can visit her website.

Leggi l’intervista in Italiano qui.

- Hair an american Tribal love rock musical - 8 Aprile 2025

- Heather Cornell: la tap dance è musica, teatro e danza - 21 Gennaio 2024

- Heather Cornell: tap dance is music, theatre, and dance - 21 Gennaio 2024